Whenever I start a new collaboration with a composer, generally there are a lot of questions on how orchestration really works and what exactly it is that I do.

Some time ago, my friend Anne-Kathrin Dern asked me to do a video about orchestration which is posted on her YouTube channel. We talked in depth about the orchestration process, so this is a great video to check out.

Even though the majority, if not all, the information about orchestration it is included in this video, I wanted to write out some of the general ideas here.

The basics

In modern times most composers write directly into a sequencer (Cubase, Logic, Pro Tools etc.) If the music needs to get recorded with a live orchestra, an orchestrator is needed. What the orchestrator does is translate what was done in the midi into music notation, so real players can perform and record the music.

In that “translation” process, there are different things to take into account to ensure an efficient session. The goal is to record with the least takes possible and to get there, the final orchestrated score must be clear. So let’s dig into some of these details that go into the orchestration process.

- Overall check.

- Clean up.

- Import midi into notation.

- More clean up.

- Orchestrate.

- Copy parts.

- Delivery.

OVERALL CHECK

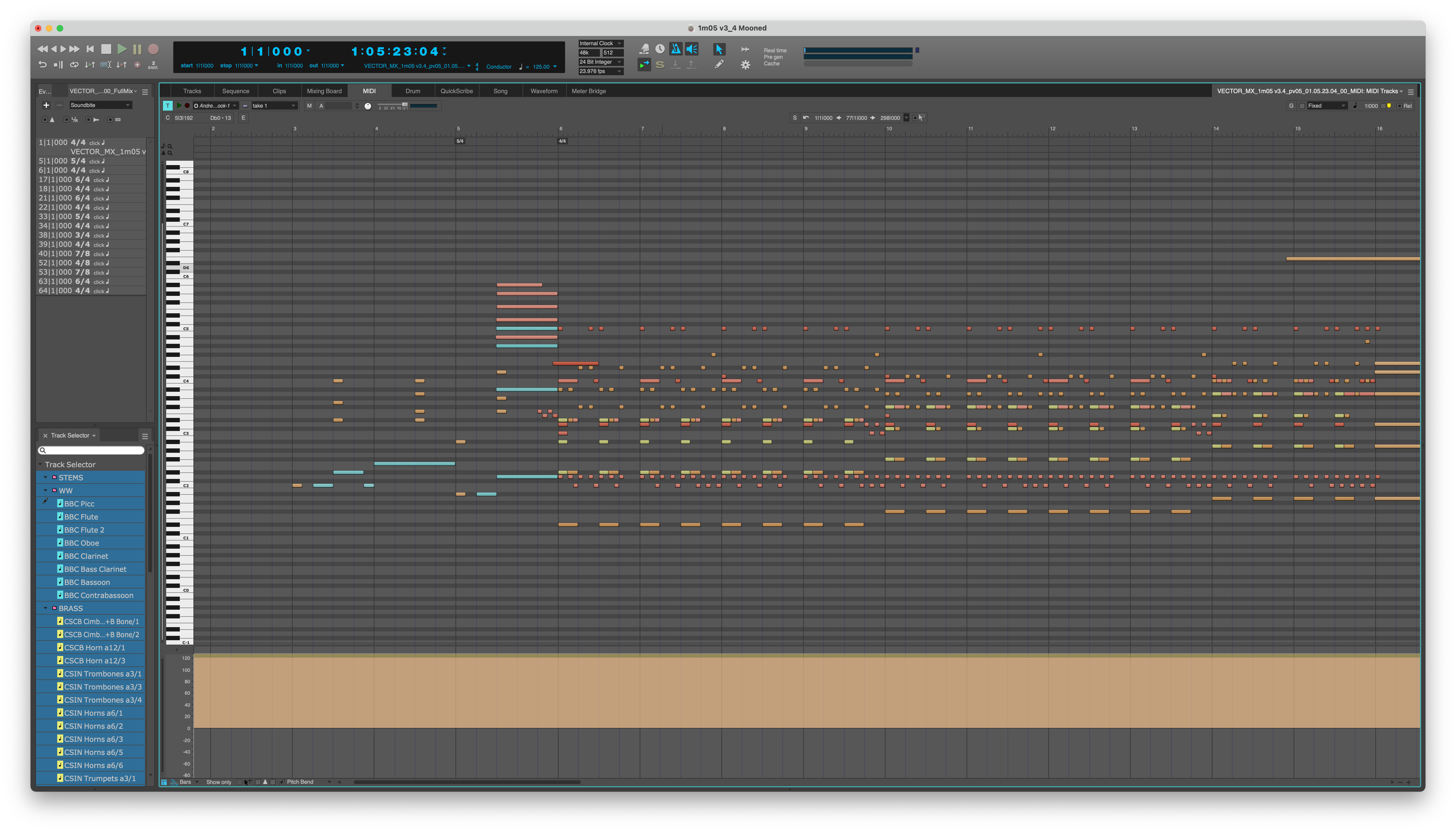

Once I receive the midi and the stereo mix, I create a sequence in Digital Performer. During this process I check that the midi lines up with the audio and that data is not missing. Then I check that the time signatures and the tempo map work for live performance. If the tempo map doesn’t work as it is, I will adjust it. And just to be clear, all these adjustments will not change the timing with the picture, so it will not get out of sync. The changes are merely technical and for notation purposes.

clean up

After the overall check, I start cleaning up the midi in my sequence. This means to quantize 100% to the grid every single note. Attacks and releases. This process ensures that the rhythms will be notated correctly once I import the midi into the notation software.

IMPORT MIDI INTO NOTATION

When I’m done quantizing the midi, I import it into Sibelius, which is my preferred notation software. (Finale used to be my go-to, but not anymore… but that’s a topic for another blog!)

more clean up

Now the data is in Sibelius. In this step I check that the rhythms are written correctly. I check that enharmonics match up and down across all the sections in the orchestra and I condense the data to remove staves that could be combined. For example, combine all articulations such as shorts and longs, etc., in the least amount of staves. And finally adding articulations that change the sound of the instrument. For example pizzicatos, tremolos, trills etc. The result is a sketch that represents the data of the mockup in a concise and accurate way.

orchestrate

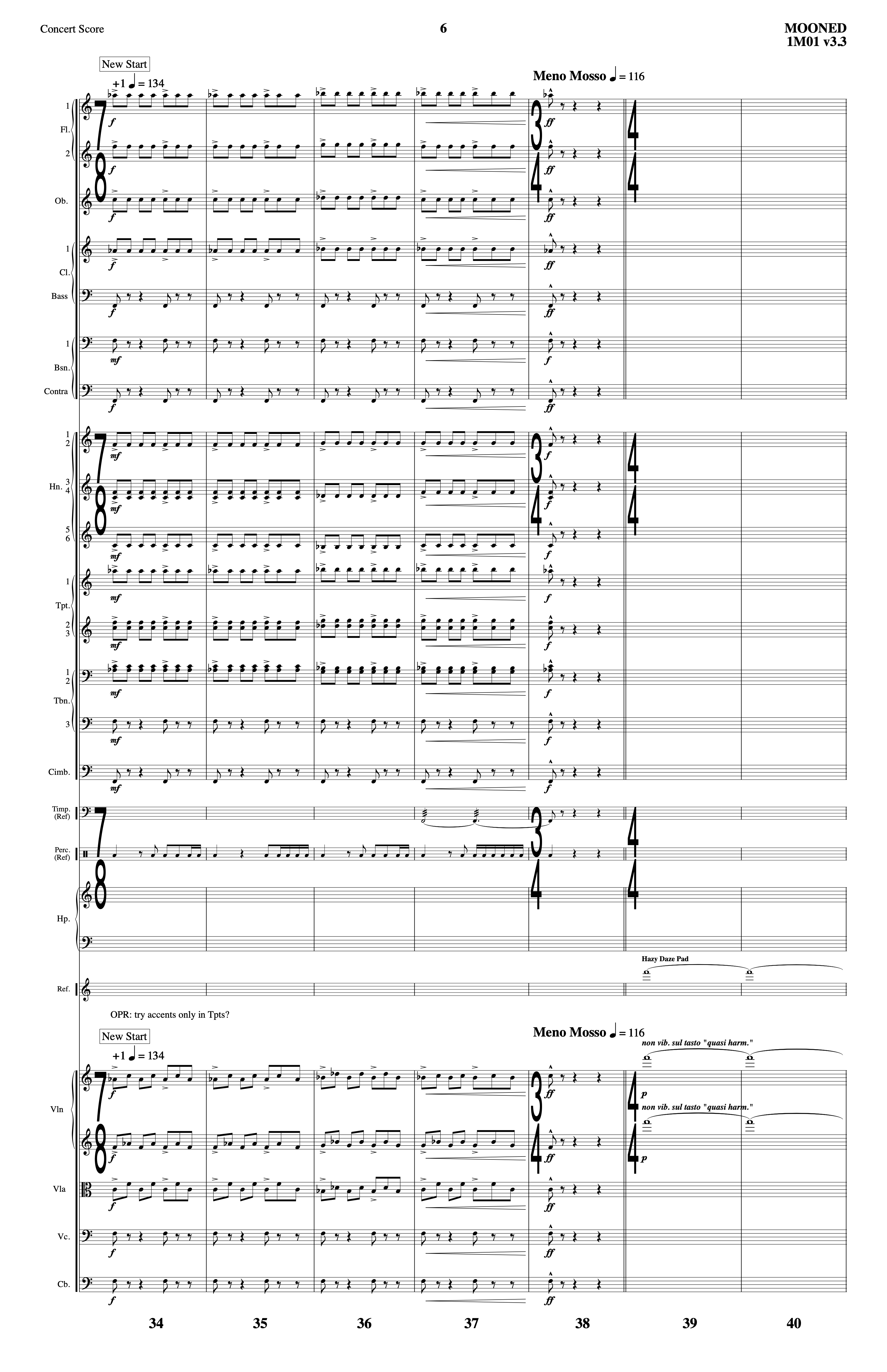

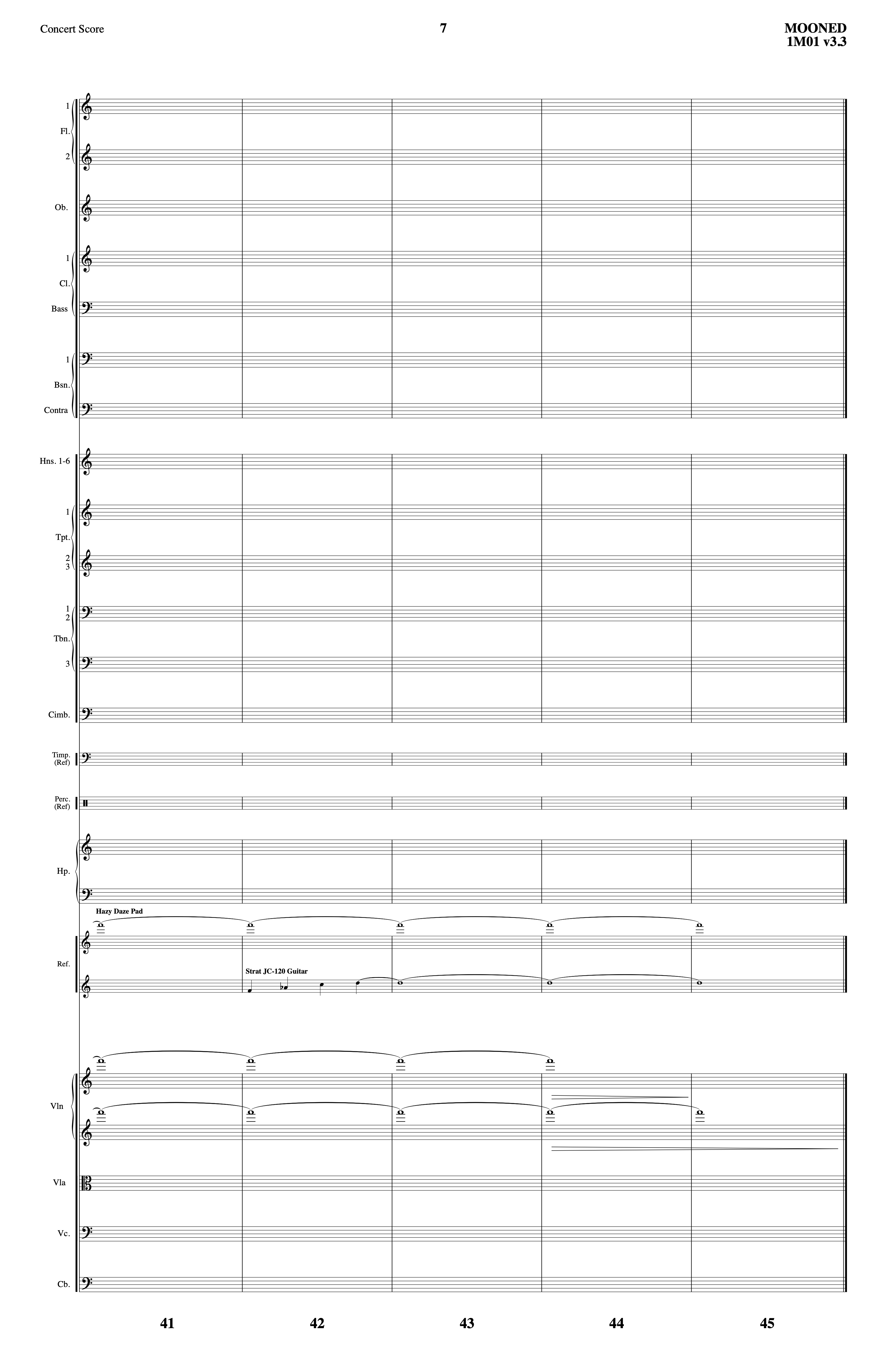

This is the process where the score is actually being done. I add dynamics and articulations. I check all the voicings and adjust them as needed and I flesh out the score where I find room to do so. As I mentioned before, the goal is to translate what the composer has done in the midi into the real orchestra, so when we get to the scoring stage, we hear what it was in the mockup, but better! On a more technical side, once the orchestration is done, I work on the layout so the score is easy to read and follow. I make sure that I’m not missing anything (notes, time signatures, tempos, double bars etc.) to create a seamless experience for the conductor and the players. Let’s not forget that musicians will read the music for the first time that day. A smooth session maximizes the time and money that’s put into a recording session.

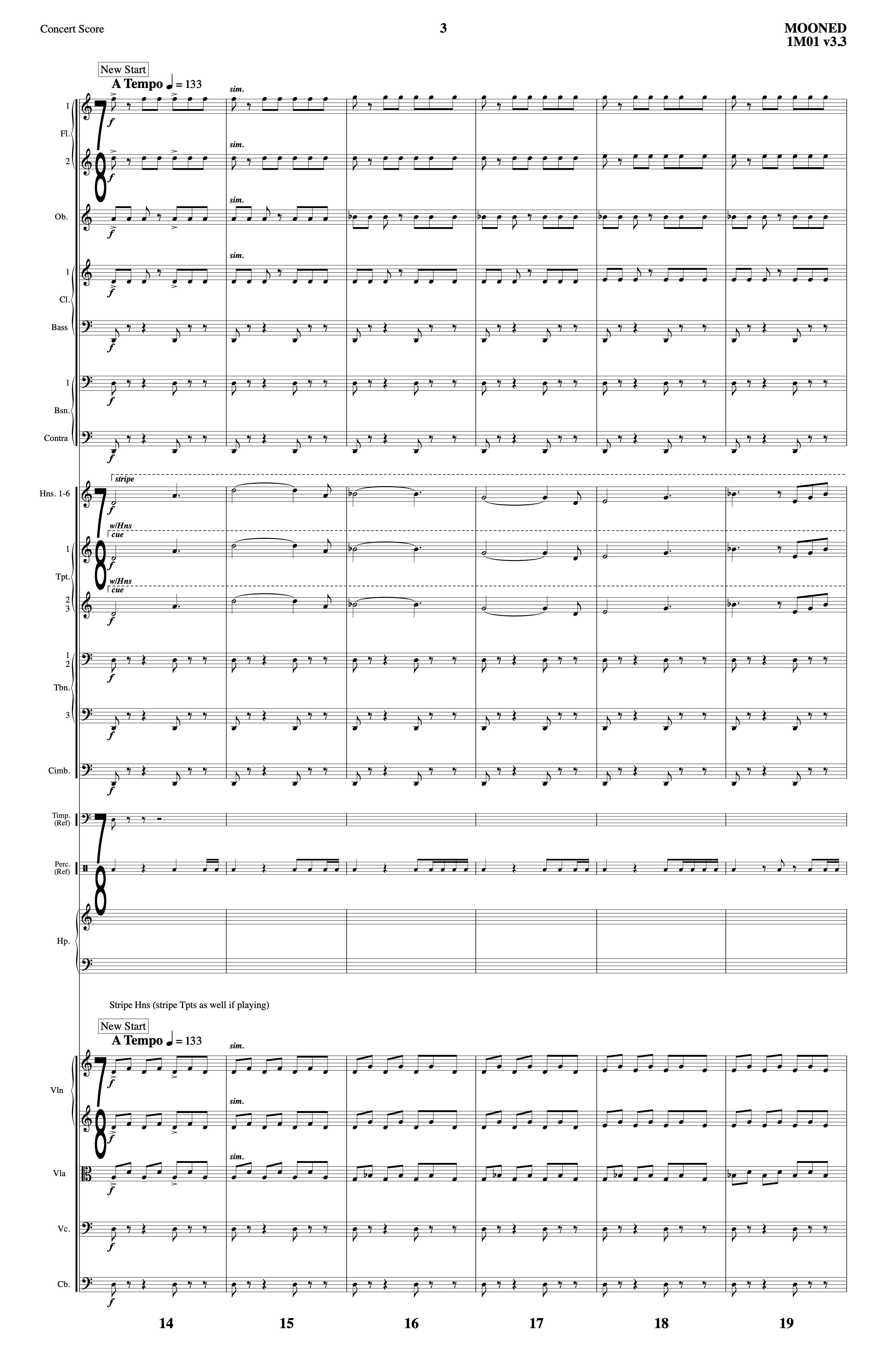

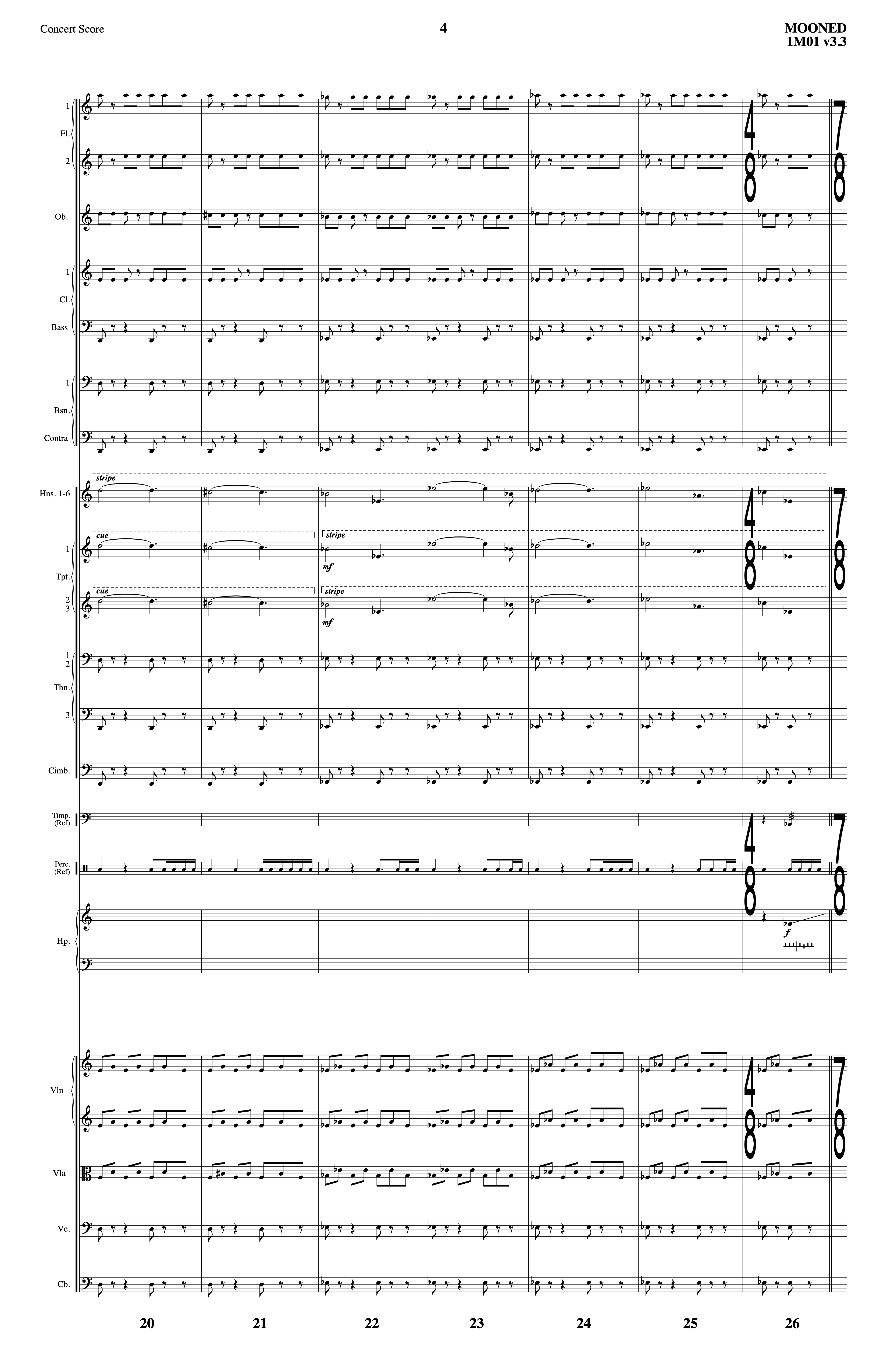

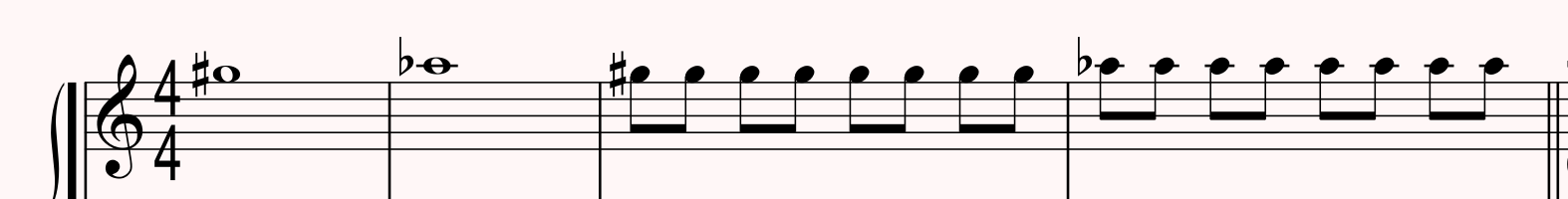

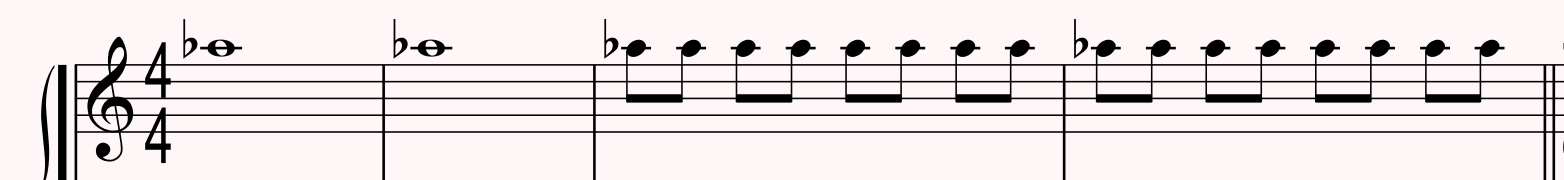

Here’s an example of a score I orchestrated for Mooned, a Minions short film (it played in theaters opening the Migration movie) composed by Orlando Pérez Rosso. For this project we recorded around five minutes of mostly action music in a one hour slot. Take a look and listen to the score below.

COPY PARTS

With the score done, an independent part for each player or section is created. During this stage it is crucial to determine the layout of the part so it’s easy for the player to read. In each part I might change enharmonics for sight-reading purposes. For example (see screenshot below), while doing the score I may have an Ab major chord and the next chord is E major. Let’s say the violins are playing Ab (on the Ab chord) and on the next measure the violins re attack the note, this time playing a G# (on the E major chord). Ab and G# are enharmonically the “same note”, but it could be confusing for a player reading the part to have Ab and then G#. Of course, the musicians could figure it out, but in a fast pace environment of a recording session I want to minimize any confusion or “double” thinking a note when I can quickly prevent that while making the part.

DELIVERY

If the session is outside of Los Angeles, I deliver PDF files of the score(s) and parts to whoever is going to print them. If the session is in LA, I deliver the score and parts printed.

RECORDING SESSION